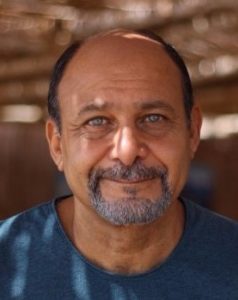

33 years ago, a man decided to leave all the fortunes that life bestowed upon him in chase of one dream: freedom.

via Sherif El Ghamrawy

Sherif El Ghamrawy, a German-educated engineer, realized in his mid-twenties that he wasn’t meant to be a prototype. He always hated the term ‘by the book,’ and as he phrased it to me, “I curse the person who invented this term; generations were lost to this illusion of rationality.”

Before conducting my interview with El Ghamrawy, I had typical prospects in mind. I assumed a great extent of resemblance to the success stories I luckily had the chance to cover. But no, to me, this was unlike any other. This specific story binds belonging, determination and most importantly, nonconformity in a long-standing consistent society.

Having built a fine reputation in the field of contractors whilst also owning his own office, El Ghamrawy almost had everything going for him. But it wasn’t long enough before he decided to migrate to Egypt. Yes, Egypt, that’s exactly what he said. I reiterated what he told me, “Migrate to Egypt, you said?” with a hushed giggle. “Yes dear, Egypt,” he confirmed.

He went on to explain that people mistakenly confuse Egypt (or Masr) with Cairo. Egypt, to El Ghamrawy, wasn’t confined to Cairo’s premises. Amid his mystical adventurous migration to Egypt and his bewilderment of where exactly to settle, he found what he calls treasure; he found Ras Burqa, in the district of Nuweiba.

With his mind wide open, El Ghamrawy found his calling to bring to life a new place called Basata in Ras Burqa. That new gem fulfilled the true meaning of tourism and cultural exchange. “Our resourceful culture was too precious not to be rightfully exposed to the outside world,” he said to me.

via Basata Eco-lodge

With very little capital and “crazy” as a nickname, El Ghamrawy started to work towards a dream, he himself only believed in, from 1982 until its actual creation in 1986. Throughout those four years, El Ghamrawy was put down and halted constantly, especially from the government’s side. There was no law back then to regulate or manage the buying and selling of lands located along the Sinai Peninsula. The obstacles he faced were not easy to overcome. He even recalled that a governor at the time told him, “As long as I’m occupying this position, your project will never see the light of day.”

What brought him down even more, was that time when he went on the radio to articulate the inflexibility that the youth were facing, and the head of Ministry replied to him saying, “Your problem is that you’re trying to take the ladder from the top, unlike everyone else.” He didn’t understand how that was so, even though he was starting a business literally from nothing.

El Ghamrawy refused to give in to these setbacks and had one thing ahead of him: I will make it happen. And in 1986, he was able to find the place of his dreams, pulling a tongue out to all his knockers. But the dream started to even get bigger when he got married to his German wife, Maria, whom he now says is more Egyptian than any of us.

via Basata Eco-Lodge

“We, men, are shortsighted. Thank God women exist,” El Ghamrawy said to me. When they had their first baby, schooling became an issue. It was either they go back to Cairo, which was a no-go, or Maria goes on her own with the kids, and that also was a big NO to him. So, what came out of this problem was a solution which was an actual school in Basata. That school started with four Bedouin kids, including their daughter. This all happened 22 years ago, to what has now become a normal operating school like any other.

What makes Basata’s community different, is that everything about it is Egyptian. From the mud bricks, the food, the environment, to literally every single little detail. To El Ghamrawy, nature is so valuable to ever be destructed humans. “The land owns me, not the other way around. One day I’ll leave but the land will always stay,” he said to me. El Ghamrawy believes that we are guests on this planet, therefore we should pay it back by respecting it.

Therefore, along with his decision to make the existence of Basata a reality, he founded an environmental NGO, Hemaya. Hemaya, located in Basata, has been operating for the past two decades, for the sole purpose of protecting the environment and reviving social development. “We collect organic and inorganic remnants along the Gulf of Aqaba, where we give the organic to the Bedouins and take the inorganic ones to a station. All minerals get separated to be sent back to Cairo for recycling. Hemaya is also responsible for the cleanliness of Dahab and Nuweiba, along with Dahab and Taba hospitals’ maintenance,” said El Ghamrawy.

via Basata Eco-Lodge

When I thought the story was over, El Ghamrawy surprised me and told me there that was more yet to come. He continued by telling me that what he did next, was a payback favor for the amazing people of Nuweiba, that considered him and his family part of them. El Ghamrawy rented two houses in Nuweiba’s Tarabeen; one to become a cultural center and the other to be a house dedicated to women, where they gather to meet, receive workshops in the afternoon and a kindergarten with teachers for their kids in the morning.

El Ghamrawy is still residing in Basata with his family, living the dream he pictured 33 years ago.

El Ghamrawy and his family — Via Basata Eco-Lodge

“Egypt is full of opportunities but we’re too busy to see them because we’re so blinded by what we were taught to do, rather than what we want to do. Egypt is not Cairo, it’s not the government, and definitely is not anyone’s but ours,” El Ghamrawy said to me as our sit down was coming to an end.